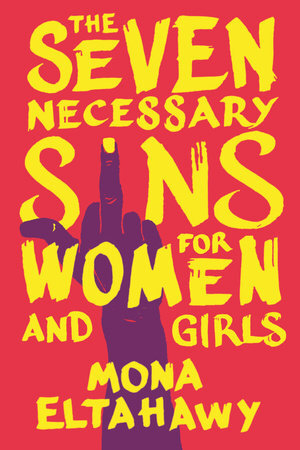

“Feminism is my lived reality” Mona Eltahawy’s Seven Necessary Sins to Fight Patriarchy

Giant feminist writer Mona Eltahawy starts all her talks with her declaration of faith: “Fuck the Patriarchy”, whether she is in Lagos or in Amsterdam or New York City, she wants patriarchy to fear feminism everywhere across the globe, and for that, we need feminist warriors.

Interview by Canan Marasligil for De Nederlandse Boekengids.

“I want to bottle-feed rage to every baby girl so that it fortifies her bones and muscles”

Photo by Robert Rutledge

Sekhmet, the ancient Egyptian goddess of retribution and sex, adorns the inside of one of Mona Eltahawy’s forearms, while ‘Mohamed Mahmoud’ the name of the street where she was attacked in November 2011 during the Egyptian revolution, next to the word ‘freedom’, defy the scars that were left there when she was sexually assaulted by the police. They broke both of her now tattooed arms. In 2012, Eltahawy wrote about this violent assault in a powerful piece for Foreign Policy, “Why Do They Hate Us?” which she expanded into her first book Headscarves and Hymens. Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution. Eltahawy is now back with her second book: The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls and has already started working on her third: A Feminist Giant’s Guide to Losing your Virginity.

“This second book starts where Headscarves and Hymens is stopping. I end Headscarves with ‘I own my body’, and that book was about the Middle East and North Africa, Seven Necessary Sins is about the whole world. And I end it with lust because the next book I want to write focuses on queerness and sexuality. It was all very intentional, also with an eye on the next book. All together these books look at what I call the trifecta of misogyny: the state, the street, the home.” Both Headscarves and Hymens and Seven Necessary Sins offer a comprehensive account of internalized misogyny, sexual harassment, domestic violence, gender politics and women’s rights, leaning on facts and the painful stories of so many women, yet, these books are also deeply personal.

Photo by Robert Rutledge

“I want to show women that it’s okay to feel vulnerable and to experience pain, but I also want to show it in a way that says: I’m here. It’s a very delicate balance. I’m speaking as I’m thinking. When people tell me I’m brave, I tell them I don’t wake up in the morning thinking; I’m going to be brave. That’s not how it happens. It’s important to show that mix. ”

“I want to bottle-feed rage to every baby girl so that it fortifies her bones and muscles,” Eltahawy writes in Seven Necessary Sins. Her rage for justice informs each sentence of her work, and because she speaks from an authentic place, she shakes you to the core. The strength of her writing, her social media presence and many appearances in festivals and in the media, is that she manages to bring the scope of the work to a much wider geographical level, reminding us that patriarchy affects every one of us everywhere, and that our battle against it is global.

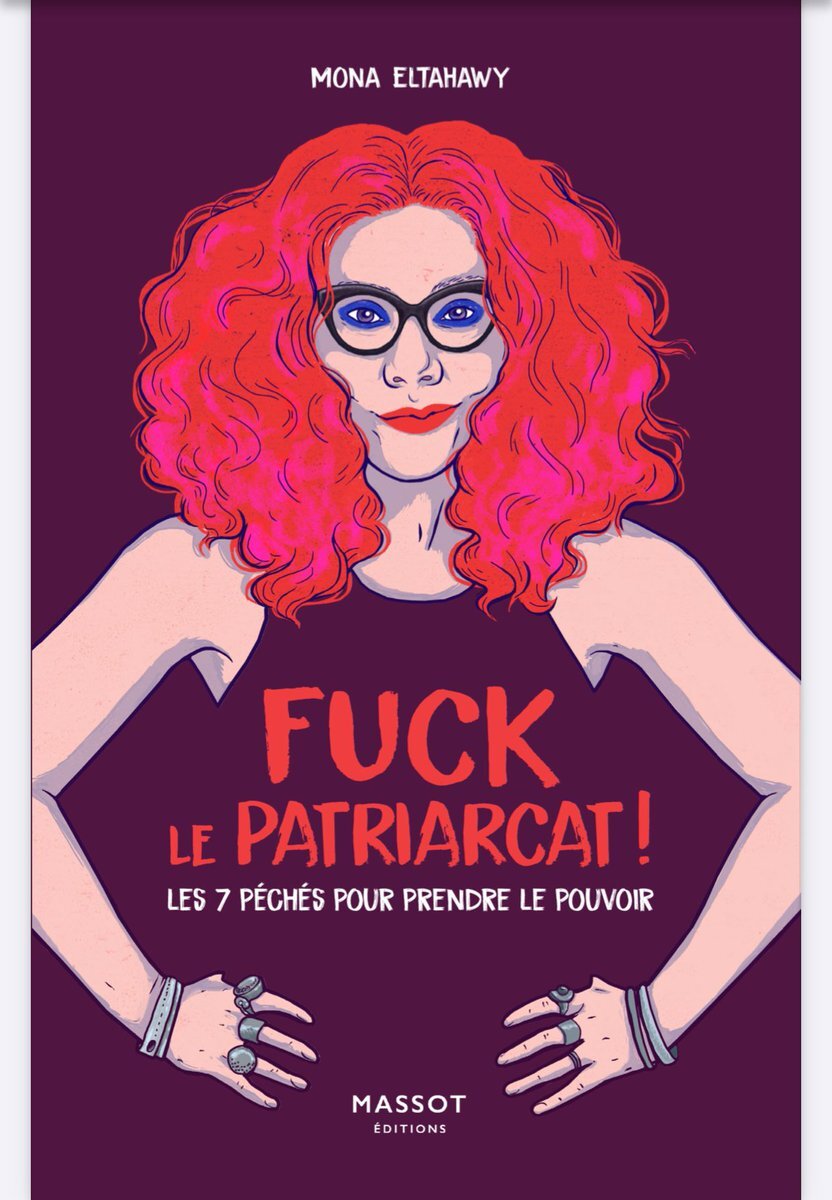

All the seven sins in her book go beyond discourse into the whole body and they all feed into each other, bringing the body into spaces to make change happen. Through her activism, her online presence, the way she expresses herself through her hair, with her tattoos and outfits, Eltahawy brings her body into the discourse, and all those sins feed into who she is and what she stands for. “One of my biggest problems with contemporary feminism is that it seems to be stuck in the cerebral and the intellectual, and I think that makes it ineffective – of course the intellectual and the cerebral are important and we need our feminist intellectuals and we need our feminist thinkers, but without connecting the thought with the body, without connecting the intellect with the physical, I think that we lose so much.”

Eltahawy was reminded of this with something she started to do recently at events, “at the end of my talks I asked the audience to stand up, and at the count of three to yell ‘Fuck the Patriarchy’. I started this in Lagos with about 250 people in the room, and it was incredible, and I did it again in Melbourne town hall with an audience of about a thousand people! In Lagos everybody loved it, the air was electric, people were coming up to me and wanted to record videos with me saying ‘Fuck the Patriarchy’ and doing pictures with middle fingers up, it’s a very different crowd. And this links to cultural context and the specificities of places. And then when I did it in Melbourne, people were also really excited about it, many people posted videos. But I was reading a feminist online magazine where their journalist talked about five highlights from the feminist festival where I spoke, and it was really interesting to see her reaction to this, she said: ‘while I appreciate Mona Eltahawy’s abrasiveness and profanity, the way that she ended the panel felt very performative and I’m not a fan of performativity’. And this is where I part ways with her. Feminism cannot be stuck in the brain; it cannot be stuck in our heads. I want feminist warriors; I want patriarchy to fear feminism. They’re not going to fear us with just ideas, they need to see the physical thing in front of them.” This same journalist also criticised her for preaching to the choir, but it doesn’t matter, Eltahawy says, “It’s still important. Why do people go to church, to concerts, to congregational things? When I go to a club, I know everyone there loves dancing, does it make dancing any less effective? When I go to a church or a synagogue or a mosque, everybody there is already the choir. They all already believe. Does it make it less impactful? Of course, it doesn’t.”

“The revolution needs joy, because if the revolution doesn’t have joy, what is the fucking point?”

Photo by Robert Rutledge

We talk further about performativity; how public speaking is a form of performance and how it fits into feminism. Eltahawy explains that when both her arms were in casts for three months, she couldn’t write and thought of ways to get her message across. “My body became a canvas that I used again to move through the world and the word. Afterwards, I rewarded myself for surviving: but not in a private way. I decided to die my hair red, because red is such a ‘fuck you, you didn’t kill me I survived colour, and here I am, I’m not hiding I’m not scared’, and I got tattoos on both of my arms. Because I wanted permanent marks of my choosing. I didn’t choose sexual assault, it was done against my will, and I didn’t choose the scar of my body that resulted from the surgery. Bright red hair, tattoos… that became a way to use my body as a canvas. And I moved back to Egypt like this, to tell the regime fuck you I’m not scared I’m here and you can find me. And that’s how I make it a daily reality, it’s not like I’m going to wear my red hair from 9 to 5 then go back to black hair anymore. This is me now. I’m on all of the time.”

The music, the books, the outfits all come together in this way, “I’ve now begun to wear sequins more and more, which sounds incredibly frivolous, and it’s all about sparkles and what little girls love, and you know what, I love little girls! Little girls are really important. People have this ridiculous prejudice about pink for instance, but for fuck’s sakes stop talking about pink. I love pink! There’s so much more to talk about.” Eltahawy concludes that you don’t need to look miserable to be an activist or to be taken seriously, and she adds that another important thing she wants to write about is the importance of joy. “The revolution needs joy, because if the revolution doesn’t have joy, what is the fucking point?” That’s how all come together in the seven necessary sins.

The order of the sins is very important and intentional, it starts with anger and ends with lust. “We see so many books coming out about anger, with white women suddenly discovering anger, and we are like ‘where the fuck have you been?’ We’ve been angry for such a long time.” Eltahawy also touches on the stereotypes of the “angry black woman” and the “angry feminist”, and warns on the weakness of a feminism that would only pay attention to misogyny, such as we have experienced in the post-Trump era: “many white women only pay attention to just misogyny because they have the privilege to pay attention to just misogyny. Anger is, like Audre Lorde says, the fuel that drives the engine. But it has to take you somewhere. We can’t just be angry. If I was only an angry person, I couldn’t do half of what I achieve. Anger is what drives us. And I started with anger too because when I first wrote this essay about how to nurture anger in little girls, people would come to me saying little girls are born with anger, we don’t need to teach them anger. I know that, but we do something to little girls that break the anger in them. I began with anger because I recognise that little girls are born with anger, but at one point we break them. I compare this to domesticating a wild horse. And we start that at the age of 10, around the world regardless of their cultural context, just like the study I mention in the book shows. Anger had to be the beginning and not the end.” After Anger come: Attention, Profanity, Ambition, Power, Violence and Lust. Every sin builds up on the one before, “lust had to come in the end, because lust represents the culmination of all of them, including power, violence…”

Eltahawy is an empowering voice for countless people through all the work she does, also beyond her writing, fighting daily against exclusion, undemocratic practices and ideas, globally. When talking about attention, she says that in the past, she wouldn’t want any, focusing on the ideas, “But now I’m like, yeah, fuck you I want attention, my ideas are important.” She uses Twitter in an insightful way to raise awareness on key issues such as female genital mutilation or violence against women and LGBTQ+, and, to foster solidarity. While doing so, she is also forced to – such is the unfortunate reality of Twitter – respond to the numerous trolls that try to silence her daily. All of this work takes a lot of energy and pain, and requires showing vulnerability, to put oneself out there naked and the responses are not always gentle. “It’s necessary to talk about this and show to younger women that vulnerability is important. We’re not these impenetrable beings that are just unfeeling, unresponsive and always strong. I mean I am a very strong person, but when I look back at the past 10-15 years, most of the things I was attacked for, 7 years later people were starting to say them. And I was like, hold on a minute, when I was saying this 7 years ago you gave me shit and now you get it? So much about Israel-Palestine, about the Egyptian revolution, about patriarchy, religion, sex… in the beginning I used to take it very seriously. A few years ago, I even took a break from Twitter because this was too much, people were intentionally misinterpreting what I was saying. But that break lasted five minutes because people started saying that I finally shut up and went away. That’s when I thought: no way I am going to give my enemies any kind of pleasure in thinking that they silenced me. I realised that every time I had to show vulnerability, I had to show it in a very strong way, which sounds like a paradox, but it’s real. Because I want to show women that it’s okay to feel vulnerable and to experience pain, but I also want to show it in a way that says: I’m here. It’s a very delicate balance. I’m speaking as I’m thinking. When people tell me I’m brave, I tell them I don’t wake up in the morning thinking; I’m going to be brave. That’s not how it happens. It’s important to show that mix. For instance, when I see a #metoo story coming along, so many people share their stories in a way as if they were breaking down over and over again. The stories are not shared with rage, they show a great deal of pain and sadness and almost like retraumatising. How many times are we going to cut through this metaphorical sadness and just bleed?” This is how Eltahawy decided to share vulnerability but with strength, especially as many people would come to her asking how they could be as powerful and confident as she is. “There must be something in the way I portray vulnerability that gives them this idea of powerful vulnerability.”

Photos by Robert Rutledge

“My body became a canvas that I used again to move through the world and the word.”

The chapter on Ambition starts with a quote from Mindy Kaling saying that people feel very uncomfortable around women who don’t hate themselves. Loving oneself is key in Eltahawy’s work and whole expression as well, this is how she manages to maintain this paradox between strength and vulnerability, “I developed an incredibly deep sense of self. I love myself. I really do. That’s why I love that quote from Mindy Kaling. I don’t hate myself and I love myself very much. In the chapter on attention when people ask me who do you think you are, I answer that I think I’m one of the most important feminists in the world today. That’s who I think I am. It may seem arrogant but fine. I want young women to see this and think they can be like that too, and don’t only see the pain, so they can say: I want this. This also comes because my family and I had difficulties along the way, there was a time when they stopped speaking to me when I talked about having sex before marriage. We’ve moved beyond that because when I was assaulted in Egypt, they thought I was dead. They realised they could have lost me. They also realised that this is so serious to me that I am willing to risk my life. And that’s also why I love sharing pictures of my family on Instagram, because although we are very different, I want to show that we are here. My mother and my sister look very different from me but here we are. The same goes for my relationship with Robert, when we talk about relationships we talk as if romantic relationship or marriage comes before everything else, but it’s not what I do.”

Throughout the years, as Eltahawy’s life, thoughts and work developed, she has been identifying herself as queer and polyamorous, “How I define and live queerness has become much more sophisticated since my relationship with Robert. Because when we first met, very early on he told me he is bisexual, and I told him I was polyamorous, and since we’ve got to know each other more over the past five and a half years, learning about his bisexuality has helped develop my queerness, as I think me being polyamorous - and you’d have to ask him of course – developed how he thinks about relationships. I’m at a stage when I’m done with straight cis men. Being in a relationship with someone who has rebelled against heteronormativity has given me so much strength in my own fight against heteronormativity. That’s where the third book comes in. There are multiple layers of relationships that have helped me when I’m vulnerable, showed me love, in the ways I resist and rebel, and have seen all the different parts of me in their paradoxes. It’s not an easy answer.” If the chapter on Ambition starts with a quote from Kaling, it ends with a beautiful and very moving exchange with Eltahawy’s niece. Another example of how vulnerability and strength come together, through love shared inside her family.

In her chapter on Profanity, Eltahawy quotes queer Chicana poet, writer and feminist Gloria Anzaldúa: “Writing is dangerous because we are afraid of what the writing reveals: the fears, the angers, the strengths of a woman under a triple or quadruple oppression. Yet in that very act lies our survival because a woman who writes has power. And a woman with power is feared.” She herself always seems fearless when she talks, but I ask her what happens when she sits down in front of a blank page, if she ever gets scared of what she will write down: “Definitely! One thing I keep writing in my notebooks, also as I started to think of book three, I keep writing ‘how brave do I want to be?’ I shared already a lot and exposed so much. But I’m still asking myself ‘how brave do I want to be?’ And I want that question to always be there to challenge me. When I talk about politics, I look back at June 2005, when protests took place against the regime in Egypt which was something quite new then, because there were protests for things happening ‘over there’, for Palestine or against the war in Iraq, but now it was against our own regime. And one of the things that was being said over and over was: ‘we’re breaking the barrier of fear’, and I love that idea. I will always remember fifty of us were walking through Shobra in Cairo, and people were looking at us like we were insane. It was also a way for us to show them they can do it too. But this is against the state, and my fight isn’t just against the state but also against the street and the home. That’s why I need to be brave and break the barrier of fear against the state, the street and the home. I cannot ask young women, non-binary people, gender diverse people, queer people, to be brave unless I am brave. In the same way I will never tell someone to protest. They have to decide for themselves if they can and want to protest. I’ll never tell someone to come out, tell about their sex life or express their queerness more, unless I do. I’m breaking my own barrier of fear, and hopefully inspire people to break their own.”

subscribe to Mona Eltahawy’s newsletter The Feminist Giant, follow her on Twitter and Instagram

This interview with Mona Eltahawy was published in Dutch in de Nederlandse Boekengids in March 2020. It is published here in English for the first time in April 2021.

Writer, Literary Translator, Artist based in Amsterdam.

Canan (she/they) publishes a newsletter and podcast titled The Attention Span, taking the time to reflect, to analyse and to imagine our societies through writing, art and culture.